Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate and contribute to covering our server costs in 2024. With your support, millions of people learn about history entirely for free every month.

$ 15666 / $ 18000

The , also known as the Coercive Acts, were five laws passed by the Parliament of Great Britain in 1774 to punish the Thirteen Colonies of British North America for the Boston Tea Party. Though the acts primarily targeted the town of Boston, Massachusetts, they caused outrage throughout the colonies and helped spark the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

Parliament hoped to make an example out of Boston and targeted the town in the first three of the Intolerable Acts. These included the Boston Port Act, which closed Boston's port to commerce until the British East India Company was fully compensated for the destroyed tea; the Massachusetts Government Act which replaced the colony's elected local council with one appointed by the military governor, essentially eroding representative government in Massachusetts; and the Administration of Justice Act, which allowed British officials charged with capital offenses to be tried in England rather than in Massachusetts. The fourth act, the Quartering Act, applied to all colonies and allowed British officers to requisition unused buildings to house their men. A fifth act, the Quebec Act, is often associated with the Intolerable Acts; though it was not intended to punish the colonies, it succeeded in angering them by seemingly advancing the interests of Britain's new Roman Catholic, French Canadian subjects at the expense of the Americans.

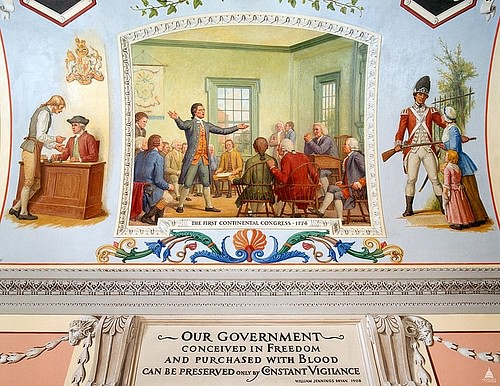

AdvertisementThe colonists responded to the Intolerable Acts by convening the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where delegates met from 5 September to 26 October 1774. Tensions caused by the Intolerable Acts would eventually lead to the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775), making their implementation one of the watershed moments of the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

By the time the Intolerable Acts were enacted in 1774, the feud between the British Parliament and the Thirteen Colonies had been raging for a decade. Asserting its role as the supreme administrative body within the British Empire, Parliament had attempted to impose a series of direct taxes on the colonies to help pay off the debt Britain had incurred during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). These taxes included the Sugar Act (1764), Stamp Act (1765), and Townshend Acts (1767-1768). Each of these taxes had been resisted by the American colonists, who argued that Parliament's attempts to tax them violated their constitutional and natural rights. Parliament was supposed to have derived its authority from the people, and since the colonists were unrepresented in Parliament, they contended that it had no power to tax them.

AdvertisementSo, beginning in 1764, the colonies resisted the Parliamentary taxes in any way they could. Colonial legislatures issued resolves in which they condemned the taxes as unconstitutional, merchants banded together to boycott British imports, and colonial thought leaders like Samuel Adams and John Dickinson wrote newspaper columns and pamphlets warning that 'taxation without representation' was tantamount to enslavement. Sometimes these protests would take physical form, which happened most frequently in the town of Boston, the capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Spurred on by an organization of underground political agitators calling themselves the Sons of Liberty, Bostonian mobs would terrorize tax officials by hanging them in effigy and ransacking their homes. Tensions only escalated when British soldiers were sent into Boston to restore order in 1768, reaching a crescendo two years later with the Boston Massacre. The killing of five American colonists by nine British soldiers sent shockwaves of anger throughout the colonies, deepening the rift between the mother country and her children.

For various reasons, all three Parliamentary acts were eventually repealed or replaced with less troublesome policies. However, Parliament ensured that it never relinquished its power to tax the colonies; such authority was enshrined in the Declaratory Act of 1766, in which Parliament asserted its right to issue binding legislation for every British colony "in all cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118). In 1770, the new ministry of Lord North rescinded all Townshend taxes except for one: a duty on tea. This singular tax was kept in place as a reminder of the authority Parliament wielded, but also as a source of revenue to pay the salaries of colonial officials; in this way, the colonial officials would become dependent on Parliament and the tea tax, rather than on the colonists they governed. The situation was worsened in May 1773 when Parliament enacted the Tea Act, which retained the tea tax while also awarding the British East India Company a monopoly on the American tea trade.

Advertisement

This was a step too far for the colonists. The East India Company was authorized to sell the tea at a cheap price, meaning that any American who bought the tea would necessarily be paying the tea tax and would therefore be inadvertently acknowledging Parliament's authority. To colonial Patriots such as Sam Adams, the Tea Act was nothing more than a 'poison', just another attempt by Britain to strip the Americans of their liberties. So, when three vessels carrying East India Company tea arrived in Boston Harbor in December 1773, a party of colonists boarded the ships, smashed open 342 crates of tea, and dumped the contents into the harbor. This protest, which came to be known as the Boston Tea Party, was celebrated throughout the colonies; even if some prominent American Patriots, like George Washington, were secretly uncomfortable with the destruction of private property, they made sure to publicly praise the event, nonetheless. Everyone involved knew that such a grandiose defiance of Parliamentary power would not go unanswered, and as the new year dawned, the colonists held their breath as they awaited a response from beyond the Atlantic.

News of the Boston Tea Party first came to London aboard a ship that arrived from the New World on 19 January 1774; a week later, the official report of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson confirmed the rumors to be true. For Parliament, there was no question that punitive measures must be taken – the rhetoric used by the king's ministers likened Parliament to a caring father who had to discipline his unruly children for their own good. Even members of Parliament who had previously sympathized with the American position on taxation felt that the destruction of East India Company property was inexcusable. Offers from American merchants to pay for the destroyed tea and put the matter to rest were declined; an example would have to be made.

The primary target of Parliamentary retribution would, of course, be Boston. On 14 March 1774, the ministry of Lord North presented a bill that would close Boston's port to trade because "the commerce of His Majesty's subjects cannot be safely carried there" (mountvernon.org). Exceptions were made only for vessels carrying provisions for the British troops garrisoned in Boston as well as for imports of fuel and food necessary for the town's survival; these imports would be heavily surveilled, however. The port would remain closed until Boston had repaid the East India Company in full for the destroyed property, an estimated cost of £10,000 (worth $1.7 million in 2023). But even once this debt was paid, the port would not be able to reopen without approval from the king himself; whether George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) decided to do so would depend on if royal authority in Boston had been sufficiently restored. This proposal, known as the Boston Port Act, sailed through both houses of Parliament with minimal debate and was approved by the king on 20 May. The closure of Boston's port to commerce was slated to go into effect on 15 June 1774.

Advertisement

The Boston Port Act was only the first of five laws that the colonists quickly dubbed the 'Intolerable Acts'. The first four were passed with the intention of punishing the colonies. However, the fifth act, called the Quebec Act or the Canada Act, was not enacted with retribution in mind; indeed, Parliament had been considering it before the Boston Tea Party took place. But since the Quebec Act was passed at the same time as the four punitive acts, and because it enraged the American colonists almost as much, it is often lumped in with the other 'Intolerable Acts'. The acts were all passed between late March and June 1774 and would become known in the colonies some weeks later.

Below is a list of the Intolerable Acts, including their provisions and why each was detested by the Americans:

News of Parliament's thunderous response slowly filtered into American ports, with word of the closure of Boston Harbor arriving on 10 May. Three days later, General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, arrived in Boston; he carried with him a commission that named him military governor of Massachusetts. These tidings were ominous enough to horrify any liberty-loving colonist, even before the full extent of the Intolerable Acts became known. As ever, the bombastic voice of Sam Adams resounded throughout Boston, stirring up resistance. Adams and the Boston committee of correspondence urged all Massachusetts merchants to completely suspend trade with Britain and the British West Indies and encouraged merchants in the other colonies to do the same. In early June, the committee sponsored a "Solemn League and Covenant", in which the signees pledged to boycott any British goods imported after 31 August and to not trade with any American who refused to sign. On 17 June, Adams and his allies organized a town meeting in which the residents of Boston voted overwhelmingly against paying for the tea.

AdvertisementWhile many colonists agreed that something had to be done in response to the Intolerable Acts, there was disagreement about what that should be.

The other colonies sympathized with Boston, with Virginia's House of Burgesses going so far as to state that Boston was undergoing a "hostile invasion" (Middlekauff, 239). The other colonial assemblies, although less dramatic in their replies, rallied behind Massachusetts, understanding that if Massachusetts lost its liberties, the other colonies would as well. But while many colonists agreed that something had to be done in response to the Intolerable Acts, there was a great deal of disagreement about what that should be; colonial merchants were hesitant to implement a boycott on all British goods, as Boston had urged, afraid that competitors would snatch up business while the rest of them were boycotting.

Hoping to find a solution to this problem, the colonies decided to send delegates to a convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a meeting that was to become known as the First Continental Congress. The Congress convened on 5 September 1774 in Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia and was attended by 56 delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies; the only colony not in attendance was Georgia, which was currently threatened by an uprising of Creek Native Americans on its frontier and did not want to risk losing British military protection by sending delegates to Philadelphia. Immediately, the Continental Congress affirmed what the Stamp Act Congress had decided nine years earlier, that Parliament's attempts to tax the colonies were a violation of the Americans' rights.

However, whereas the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 had merely denied Parliament's right to tax the colonies, several delegates to the First Continental Congress wished to go even further: to entirely deny Parliament's authority to legislate on the Americans' behalf. This was by no means the majority opinion and was espoused by the most vocal radicals like Connecticut's Roger Sherman and Virginia's Patrick Henry. Yet the fact that such beliefs were being shared at all was significant, as few had questioned Parliament's place as the superintendent of the British Empire before. Equally as shocking were those who dared place some of the blame for the Intolerable Acts at the feet of the king himself; while it had not yet reached the point where the colonists were calling George III a tyrant, many both at the Congress and beyond believed the king to have been misled by his malevolent ministers. Of course, there were also more conservative delegates who wanted to do nothing more than get the Intolerable Acts repealed and return to the status quo.

When the First Continental Congress adjourned on 26 October 1774, it appeared to have achieved its primary goal. It had agreed on a general boycott of British imports slated to begin on 1 December 1774 and had pledged to suspend exports to Britain as well, if the Intolerable Acts were not repealed by 10 September 1775. If the situation did not improve, the delegates agreed to reconvene in April 1775. By that point, however, the situation would have spun out of control; 19 April 1775 would see the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, which would begin eight years of armed conflict with Britain. The strife caused by the Intolerable Acts, therefore, was one of the immediate triggers of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and helped set the colonies down the road to independence as a new nation, the United States of America.